Argument Intent Linter

The previous notebooks have all focused on using Loki to perform code transformations. Loki can also be used as a Fortran linter. In this notebook, we will use Loki to check whether the declared intent of a subroutine argument is consistent with how that variable is used.

For brevity, only the core functionality of a subroutine dummy argument intent-linter is developed here.

Let us start by first examining the sample subroutine that we will use to illustrate this notebook:

[1]:

from loki import Sourcefile

source = Sourcefile.from_file('src/intent_test.F90')

print(source.to_fortran())

MODULE kernel_mod

USE parkind1, ONLY: jpim, jprb

IMPLICIT NONE

CONTAINS

SUBROUTINE some_kernel (n, vout, var_out, var_in, var_inout, b, l, h, y)

INTEGER(KIND=jpim), INTENT(IN) :: n, l, b

INTEGER(KIND=jpim), INTENT(IN) :: h

REAL(KIND=jprb), INTENT(IN) :: var_in(n)

REAL(KIND=jprb), INTENT(INOUT) :: var_out(n)

REAL(KIND=jprb), INTENT(INOUT) :: var_inout(n)

REAL(KIND=jprb), INTENT(INOUT) :: vout(n)

REAL(KIND=jprb), INTENT(INOUT) :: y(:)

END SUBROUTINE some_kernel

END MODULE kernel_mod

SUBROUTINE intent_test (m, n, var_in, var_out, var_inout, tendency_loc)

USE parkind1, ONLY: jpim, jprb

USE kernel_mod, ONLY: some_kernel

USE yoecldp, ONLY: nclv

IMPLICIT NONE

INTEGER(KIND=jpim), INTENT(IN) :: m, n

INTEGER(KIND=jpim) :: i, j, k, h, l

REAL(KIND=jprb), INTENT(IN) :: var_in(n, n, n)

REAL(KIND=jprb), TARGET, INTENT(OUT) :: var_out(n, n, n)

REAL(KIND=jprb), INTENT(INOUT) :: var_inout(n, n, n)

REAL(KIND=jprb), ALLOCATABLE :: x(:), y(:)

REAL(KIND=jprb), POINTER :: vout(n)

TYPE(state_type), INTENT(OUT) :: tendency_loc

ALLOCATE (x(n))

ASSOCIATE (mtmp=>m)

ALLOCATE (y(mtmp))

END ASSOCIATE

ASSOCIATE (mtmp=>n)

DO k=1,mtmp

DO j=1,mtmp

DO i=1,mtmp

var_out(i, j, k) = 2._jprb

END DO

ASSOCIATE (mbuf=>mtmp)

var_out(m:mbuf, j, k) = var_in(m:mbuf, j, k) + var_inout(m:mbuf, j, k) + var_out(m:mbuf, j, k)

END ASSOCIATE

vout => var_out(:, j, k)

ASSOCIATE (vin=>mtmp)

CALL some_kernel(vin, vout, vout, var_in(:, j, k), var_inout(:, j, k), 1, h=vin, l=5, y=y)

END ASSOCIATE

NULLIFY (vout)

ASSOCIATE (vout=>tendency_loc%cld(:, j, k))

ASSOCIATE (vin=>var_in(:, j, k))

CALL some_kernel(mtmp, vout, var_out(:, j, k), vin, var_inout(:, j, k), 1, h=mtmp, l=5, y=y)

END ASSOCIATE

END ASSOCIATE

DO i=1,mtmp

var_inout(i, j, k) = var_out(i, j, k)

END DO

END DO

END DO

END ASSOCIATE

DEALLOCATE (x)

DEALLOCATE (y)

END SUBROUTINE intent_test

Retrieving variable intent

We can access all the variables declared in subroutine intent_test using the variables property of the Subroutine object:

[2]:

routine = source['intent_test']

print('vars::', ', '.join([str(v) for v in routine.variables]))

vars:: m, n, i, j, k, h, l, var_in(n, n, n), var_out(n, n, n), var_inout(n, n, n), x(:), y(:), vout(n), tendency_loc

In the Loki IR, variables are stored as symbols with base class MetaSymbol and the intent of a variable is stored in the property `MetaSymbol.type <https://sites.ecmwf.int/docs/loki/main/loki.expression.symbols.html#loki.expression.symbols.MetaSymbol.type>`__. To retrieve all variables with declared intent, we only need to look through the subroutine arguments:

[3]:

from collections import defaultdict

intent_vars = defaultdict(list)

for var in routine.arguments:

intent_vars[var.type.intent].append(var)

in_vars = intent_vars['in']

out_vars = intent_vars['out']

inout_vars = intent_vars['inout']

print('in::', ', '.join([str(v) for v in in_vars]), 'out::', ', '.join([str(v) for v in out_vars]), 'inout::', ','.join([str(v) for v in inout_vars]))

assert all([len(in_vars) == 3, len(out_vars) == 2, len(inout_vars) == 1])

in:: m, n, var_in(n, n, n) out:: var_out(n, n, n), tendency_loc inout:: var_inout(n, n, n)

Separating variables from dimensions

In Loki, the most general way of retrieving the variables used in an expression or node is the FindVariables visitor. In the IR nodes in the body of a subroutine, the FindVariables visitor will return variables that appear in their own right, as well as any variables used for array indexing. An example of this is seen when FindVariables is applied to an

Allocation:

[4]:

from loki import FindNodes, FindVariables, Allocation

alloc = FindNodes(Allocation).visit(routine.body)[0]

alloc_vars = FindVariables().visit(alloc.variables)

print(', '.join([str(v) for v in alloc_vars]))

x(n), n

Utilities to distingiush between variables and their dimensions can be constructed by wrapping small functions around FindVariables:

[5]:

from loki import Array, flatten

def findvarsnotdims(o, return_vars=True):

"""Return list of variables excluding any array dimensions."""

dims = flatten([FindVariables().visit(var.dimensions) for var in FindVariables().visit(o) if isinstance(var, Array)])

# remove duplicates from dims

dims = list(set(dims))

if return_vars:

return [var for var in FindVariables().visit(o) if not var in dims]

return [var.name for var in FindVariables().visit(o) if not var in dims]

def finddimsnotvars(o, return_vars=True):

"""Return list of all array dimensions."""

dims = flatten([FindVariables().visit(var.dimensions) for var in FindVariables().visit(o) if isinstance(var, Array)])

# remove duplicates from dims

dims = list(set(dims))

if return_vars:

return dims

return [var.name for var in dims]

A quick test reveals:

[6]:

print(f'vars:{findvarsnotdims(alloc.variables, return_vars=False)}')

print(f'dims:{finddimsnotvars(alloc.variables, return_vars=False)}')

assert len(findvarsnotdims(alloc.variables)) == 1

assert len(finddimsnotvars(alloc.variables)) == 1

vars:['x']

dims:['n']

Resolving associations

You may have noticed that intent_test contains several nested associations. The simplest way of dealing with these is to resolve all the associations before we begin linting the program:

[7]:

from loki import fgen, SubstituteExpressions, Associate, Transformer

assoc_map = {}

for assoc in FindNodes(Associate).visit(routine.body):

vmap = {}

for rexpr, lexpr in assoc.associations:

vmap.update({var: rexpr for var in FindVariables().visit(assoc.body) if lexpr == var})

assoc_map[assoc] = SubstituteExpressions(vmap).visit(assoc.body)

routine.body = Transformer(assoc_map).visit(routine.body)

print(fgen(routine.body))

ALLOCATE (x(n))

ALLOCATE (y(m))

DO k=1,n

DO j=1,n

DO i=1,n

var_out(i, j, k) = 2._jprb

END DO

var_out(m:n, j, k) = var_in(m:n, j, k) + var_inout(m:n, j, k) + var_out(m:n, j, k)

vout => var_out(:, j, k)

CALL some_kernel(n, vout, vout, var_in(:, j, k), var_inout(:, j, k), 1, h=n, l=5, y=y)

NULLIFY (vout)

CALL some_kernel(n, tendency_loc%cld(:, j, k), var_out(:, j, k), var_in(:, j, k), var_inout(:, j, k), 1, h=n, l=5, y=y)

DO i=1,n

var_inout(i, j, k) = var_out(i, j, k)

END DO

END DO

END DO

DEALLOCATE (x)

DEALLOCATE (y)

In Loki, an Associate statement is a ScopedNode. A ScopedNode is a mix-in that attaches to an InternalNode. It declares a new scope that sits within the Subroutine scope, but also defines a few of its own symbols. This means that the new variables declared in an Associate statement are only in scope in the body of that

particular node. Therefore to resolve the associations we can simply apply the SubstituteExpressions visitor to the Associate’s body, as shown in the previous code-cell.

Resolving pointer associations that use the => operator is a little more involved. Firstly, pointers and targets must be declared in the Subroutine specification, unlike an Associate statement which declares new symbols. It would thus be wrong to think of a pointer association as having its own localised scope. Secondly, an associated pointer can be disassociated either by exiting the encompassing scope (i.e. exiting the Subroutine), by using the

Nullify intrinsic or by assigning to NULL().

Therefore before we can apply the SubstituteExpressions visitor to resolve pointer associations, we must first determine the range of nodes over which the pointer is valid. The best way to do so is to develop a bespoke visitor:

[8]:

from loki import Assignment

class FindPointerRange(FindNodes):

"""Visitor to find range of nodes over which pointer associations apply."""

def __init__(self, match, greedy=False):

super().__init__(match, mode='type', greedy=greedy)

self.rule = lambda match, o: o == match

self.stat = False

def visit_Assignment(self, o, **kwargs):

"""

Check for pointer assignment (=>). Also check if pointer is disassociated,

else add the node to the returned list.

"""

ret = kwargs.pop('ret', self.default_retval())

if self.rule(self.match, o):

assert not self.stat # we should only visit the pointer assignment node once

self.stat = True

elif self.match.lhs in findvarsnotdims(o.lhs) and 'null' in [v.name.lower for v in findvarsnotdims(o.rhs)]:

assert self.stat

self.stat = False

ret.append(o)

elif self.stat:

ret.append(o)

return ret or self.default_retval()

def visit_Nullify(self, o, **kwargs):

"""

Check if pointer is disassociated, else add the node to the returned list.

"""

ret = kwargs.pop('ret', self.default_retval())

if self.match.lhs in findvarsnotdims(o.variables):

assert self.stat

self.stat = False

ret.append(o)

elif self.stat:

ret.append(o)

return ret or self.default_retval()

def visit_Node(self, o, **kwargs):

"""

Add the node to the returned list if stat is True and visit

all children.

"""

ret = kwargs.pop('ret', self.default_retval())

if self.stat:

ret.append(o)

if self.greedy:

return ret

for i in o.children:

ret = self.visit(i, ret=ret, **kwargs)

return ret or self.default_retval()

for assign in [a for a in FindNodes(Assignment).visit(routine.body) if a.ptr]:

nodes = FindPointerRange(assign).visit(routine.body)

for node in nodes[:-1]:

print(node)

Comment::

Call:: some_kernel

Comment::

As the above output shows, our new visitor correctly identifies all three nodes over which the pointer association applies. We can now finally proceed to resolve the pointer association:

[9]:

pointer_map = {}

for assign in [a for a in FindNodes(Assignment).visit(routine.body) if a.ptr]:

nodes = FindPointerRange(assign).visit(routine.body)

pointer_map[assign] = None

for node in nodes[:-1]:

vmap = {var: assign.rhs for var in FindVariables().visit(node) if assign.lhs == var}

pointer_map[node] = SubstituteExpressions(vmap).visit(node)

pointer_map[nodes[-1]] = None

routine.body = Transformer(pointer_map).visit(routine.body)

print(fgen(routine.body))

ALLOCATE (x(n))

ALLOCATE (y(m))

DO k=1,n

DO j=1,n

DO i=1,n

var_out(i, j, k) = 2._jprb

END DO

var_out(m:n, j, k) = var_in(m:n, j, k) + var_inout(m:n, j, k) + var_out(m:n, j, k)

CALL some_kernel(n, var_out(:, j, k), var_out(:, j, k), var_in(:, j, k), var_inout(:, j, k), 1, h=n, l=5, y=y)

CALL some_kernel(n, tendency_loc%cld(:, j, k), var_out(:, j, k), var_in(:, j, k), var_inout(:, j, k), 1, h=n, l=5, y=y)

DO i=1,n

var_inout(i, j, k) = var_out(i, j, k)

END DO

END DO

END DO

DEALLOCATE (x)

DEALLOCATE (y)

Modifying variable values

Putting aside function or subroutine calls for the moment (and also ignoring I/O), there are only two mechanisms for modifying the value of a variable. The obvious one is an Assignment statement, where the rhs value is assigned to the lhs value.

Values can also be assigned to a variable by using it as the induction variable of a loop. Although an extremely unusual practice, Fortran compilers do allow dummy arguments of kind intent(out) or intent(inout) to be used as the induction variables of a loop. This is however (in my humble opinion) bad coding practice; for ease of readability, local variables rather than dummy arguments should be used as loop induction variables. Therefore in our linter rules, we will forbid the use of

variables with declared intent as loop induction variables.

To enable us to check all our linter rules in just one pass of the subroutine’s IR, we will create a new visitor: IntentLinterVisitor. The next section creates the IntentLinterVisitor visitor and defines linter rules for checking intent consistency within the Subroutine body. We will later examine how this can be extended to subroutine calls.

Checking intent in Subroutine body

Let us first define an initialization method for an instance of IntentLinterVisitor, and a method to check for rule violations:

[10]:

from loki import Visitor

class IntentLinterVisitor(Visitor):

"""Visitor to check for dummy argument intent violations."""

def __init__(self, in_vars, out_vars, inout_vars): # pylint: disable=redefined-outer-name

"""Initialise an instance of the intent linter visitor."""

super().__init__()

self.in_vars = in_vars

self.out_vars = out_vars

self.inout_vars = inout_vars

self.var_check = {var: True for var in (in_vars + out_vars + inout_vars)}

self.vars_read = set(in_vars + inout_vars)

self.vars_written = set()

self.alloc_vars = set() # set of variables that are allocated

def rule_check(self):

"""Check rule-status for all variables with declared intent."""

for v, s in self.var_check.items():

assert s, f'intent({v.type.intent}) rule broken for {v.name}'

print('All rules satisfied')

You may have noticed that in defining our new visitor, we also introduced an attribute called alloc_vars. This is intended to accumulate the variables allocated in a subroutine. The reason for including this attribute will be clear later on.

We can now proceed to define the rules for our linter. The rule to check whether variables with declared intent are used as loop induction variables can be implemented as follows:

[11]:

def visit_Loop(self, o, **kwargs):

"""

Check if loop induction variable has declared intent, update vars_read/vars_written

if variables with declared intent are used in loop bounds and visit any nodes in loop body.

"""

if o.variable.type.intent:

self.var_check[o.variable] = False

print(f'intent({o.variable.type.intent}) {o.variable.name} used as loop induction variable.')

for v in [v for v in FindVariables().visit(o.bounds) if v.type.intent]:

if v not in self.vars_read | self.vars_written:

print(f'undefined intent({v.type.intent}) variable {v.name} used for loop bounds.')

self.var_check[v] = False

self.vars_read.add(v)

self.vars_written.discard(v)

self.visit(o.body, **kwargs)

IntentLinterVisitor.visit_Loop = visit_Loop

For intent(in) variables, we don’t want their value to be reassigned in the Subroutine. Therefore the rule for checking intent(in) variables is the simplest: variables of kind intent(in) should not appear in the lhs of an Assignment. The rule for intent(out) variables is that upon entry to a subroutine, a value must be assigned to them before the variable can be used: intent(out) variables must be written to before they can be read. For Assignment statements,

the above rules can be implemented as follows:

[12]:

def visit_Assignment(self, o):

"""Check intent rules for assignment statements."""

if o.lhs.type.intent == 'in':

print(f'value of intent(in) var {o.lhs.name} modified')

self.var_check[o.lhs] = False

self.vars_written.add(o.lhs)

self.vars_read.discard(o.lhs)

for v in FindVariables().visit(o.rhs):

if v.type.intent == 'out' and v not in self.vars_read | self.vars_written:

print('intent(out) var read from before being written to.')

self.var_check[v] = False

elif v.type.intent:

self.vars_read.add(v)

self.vars_written.discard(v)

IntentLinterVisitor.visit_Assignment = visit_Assignment

In principle we could also build similar checks for intent(inout) variables. However, the way in which some Fortran compilers treat allocatable variables prevents us from doing so.

If an allocatable array is passed to a subroutine as a dummy argument of kind intent(out), some Fortran compilers will deallocate that array upon exiting the subroutine. This is why in the IFS, data arrays are sometimes declared as intent(inout) even if their true intent is intent(out). An example can be seen in the ‘cloudsc-dwarf’ in src/cloudsc_driver_mod.F90: the REAL array PCOVPTOT is declared intent(inout) even though it’s value entering the subroutine is

never used.

An allocatable array passed as a dummy argument to a subroutine could thus belong to two possible categories: 1. A variable that is truly of type intent(inout) 2. A variable that is strictly of type intent(out), but has been declared intent(inout) to avoid deallocation

It would be very difficult to discern between the two options from a static analysis of the source code. As such, we will not impose any rules related to Assignment expressions for intent(inout) variables.

We can however impose the rule that the dummy argument corresponding to an allocatable array must be of kind intent(inout) or intent(in). To enable a visit_CallStatement method to perform this check, we first need a visit_Allocation method that updates the alloc_vars set:

[13]:

def visit_Allocation(self, o):

"""

Update set of allocated variables and read/written sets for variables used to define

allocation size.

"""

self.alloc_vars.update(o.variables)

for v in [v for v in finddimsnotvars(o.variables) if v.type.intent]:

if v not in self.vars_read | self.vars_written:

print(f'undefined intent({v.type.intent}) variable {v.name} used to set allocation size.')

self.var_check[v] = False

self.vars_read.add(v)

self.vars_written.discard(v)

IntentLinterVisitor.visit_Allocation = visit_Allocation

We are now ready to implement a visit_CallSatement method.

Building intent map between function caller and callee

We have already defined one linter rule for CallStatements; dummy arguments corresponding to allocatable variables must of type intent(in) or intent(inout). Another very important check we have to perform is to ensure that the declared intent of a dummy argument is consistent with the intent of the argument in the calling (parent) subroutine.

For example, var_in is a variable of kind intent(in) in Subroutine intent_test. Therefore var_in must not be modified within intent_test or any subroutines called by intent_test. Hence in some_kernel, var_in must also be of kind intent(in).

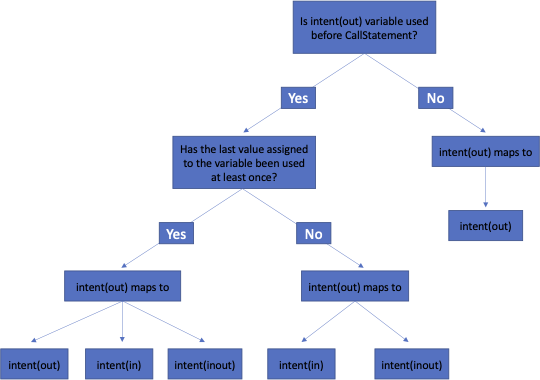

The mapping for intent(out) variables is a little more complicated and depends on whether before the CallStatement, the variable in question has ever been written to, and if so, whether the value last assigned to it has been read at least once. The procedure for building the mapping is best illustrated using the flowchart below:

[14]:

from IPython.display import Image

fig = Image(filename='gfx/intent_out_map-crop.png')

fig

[14]:

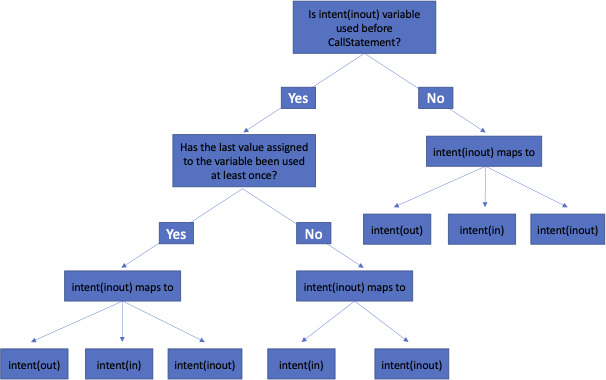

A similar process can be used to determine the mapping for intent(inout) variables:

[15]:

fig = Image(filename='gfx/intent_inout_map-crop.png')

fig

[15]:

You may be wondering why intent(out) has been included as a permitted value for the rightmost tree of the above flowchart. It is to account for the following possibility: an allocatable variable is allocated in subroutine A, and passed as an argument to subroutine B. Subroutine B must therefore declare the variable as either intent(inout) or intent(in). Subroutine B then passes the variable as an argument to subroutine C without using it first. In subroutine C, the variable can

correctly be of any declared intent.

Checking intent consistency across function calls

The code below gives an example of how a visit_CallStatement method can be implemented:

[16]:

intent_map = {'in': {'none': ['in'], 'lhs': ['in'], 'rhs': ['in']}}

intent_map['out'] = {'none': ['out'], 'lhs': ['in', 'inout'], 'rhs': ['in', 'inout', 'out']}

intent_map['inout'] = {'none': ['in', 'inout', 'out'], 'lhs': ['in', 'inout'], 'rhs': ['in', 'inout', 'out']}

def visit_CallStatement(self, o):

"""

Check intent consistency across callstatement and check intent of

dummy arguments corresponding to allocatables.

"""

assign_type = {v.name: 'none' for v in self.in_vars + self.out_vars + self.inout_vars}

assign_type.update({v.name: 'lhs' for v in self.vars_written})

assign_type.update({v.name: 'rhs' for v in self.vars_read})

for f, a in o.arg_iter():

if getattr(getattr(a, 'type', None), 'intent', None):

if f.type.intent not in intent_map[a.type.intent][assign_type[a.name]]:

print(f'Inconsistent intent in {o} for arg {a.name}')

if f.type.intent in ['in']:

self.vars_read.add(a)

self.vars_written.discard(a)

else:

self.vars_written.add(a)

self.vars_read.discard(a)

if getattr(a, "name", None) in [v.name for v in self.alloc_vars]:

if not f.type.intent in ['in', 'inout']:

print(f'Allocatable argument {a.name} has wrong intent in {o.routine}.')

IntentLinterVisitor.intent_map = intent_map

IntentLinterVisitor.visit_CallStatement = visit_CallStatement

routine.enrich(source.all_subroutines) # link CallStatements to Subroutines

In the final line of the above code-cell, we called the function enrich. This uses inter-procedural analysis to link CallStatement nodes to the relevant Subroutine objects. Also note that in the above code-cell, intent_map has been declared as a class-attribute because it will be the same for every instance of IntentLinterVisitor.

We can now finally run our intent-linter and check if any rules are broken:

[17]:

intent_linter = IntentLinterVisitor(in_vars, out_vars, inout_vars)

intent_linter.visit(routine.body)

intent_linter.rule_check()

All rules satisfied